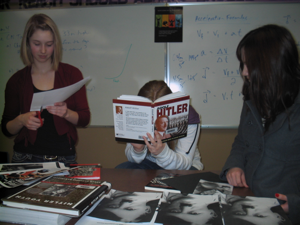

This is the sixth time I’ve taught a unit on the Holocaust, each one slightly different than the last. In the past, my students learned most of the information via lecture, notes and videos. Because I was responsible for distilling the information, I learned much more than they did. This semester they’re doing it all themselves. And the end result will be a classroom Holocaust museum curated by my grade 10 English students. The unit involves inquiry, collaborative, and project-based learning all in one.

This is the sixth time I’ve taught a unit on the Holocaust, each one slightly different than the last. In the past, my students learned most of the information via lecture, notes and videos. Because I was responsible for distilling the information, I learned much more than they did. This semester they’re doing it all themselves. And the end result will be a classroom Holocaust museum curated by my grade 10 English students. The unit involves inquiry, collaborative, and project-based learning all in one.

My role in all of this is to create an environment that is well designed and conducive to their learning. I have switched from the all-knowing guru, to the role of co-collaborator and facilitator. Since I’ve never done this before, I truly am a co-learner with my students. The purpose of this project is to provide my students with an authentic task that teaches 21st century skills, and also deepens their understanding of the events of the Holocaust.

We began by looking at the purpose of project based learning. I believe it’s important to teach my students why we are doing things, especially why we’re learning differently.

Then we discussed the purpose of the museum and their role in it. They are the creators and curators. They are responsible for everything from research to conception and design, and will serve as presentation hosts. They excitedly explored different ideas for the format, and while I allowed them to do this so they could begin to catch the vision for the project, I affirmed that the final design would emerge from the research.

Next, while sitting in a circle on the floor, each of my students took sticky notes, and brainstormed topics they thought should be part of the museum. Once finished, we posted the notes in categories to see what the recurring topics were. We were able to distil all of their ideas into three categories: the Nazis, the Jewish people, and the world’s response.

Once we outlined these three areas, we then took the topics of interest from the sticky notes, as well as a few additional areas that were suggested by the students, and outlined the specifics of each area of research. This process involved a lot more silence and waiting on my part than I would have thought. The project is based completely on their ideas and initiative, rather than having the project outlined for them. Inquiry learning is not a familiar experience for them. Instead, by grade 10, my students have learned that if they wait long enough, they will be rescued.

Not anymore.

Going Deep

After we outlined the areas, and the specific topics in each, students chose their special area of inquiry. By far the largest interest is in the Jewish people, and the world’s response. Only four students are researching the Nazis. I was surprised by this.

My students spent the first week researching both primary and secondary sources. I began by teaching the difference between the two. That was the extent of my teaching. For the rest of the week, my students scoured the internet for resources, used Delicious to bookmark important sites, and checked the credibility of sources. The first thing my students do after they log onto the computer is open their delicious accounts. I don’t even tell them to do it anymore.

Once they found a number of resources, I introduced them to Google Docs. It never fails that my students are completely amazed by this web tool. Often there are audible gasps. I’ve learned that the first day they’re inside the Google Docs environment, not much work will get done. Students are amazed by their ability to type, as a group, in the same document. They spent the rest of the week collaboratively compiling their information, important links, and photographs they’d gathered into their group’s Google Doc.

The Hard Part

Then we got stuck. Researching was the easy part, knowing what to do with it is much more difficult. The goal of week three is to construct a mock-up of their exhibit. My students struggled immensely with how to take their research and create an exhibit. What information do they use? What do they want to be their focal point? What story do they want to tell?

It’s not that they don’t have good ideas. They have some great ones. As I walked around, I heard some incredible proposals, such as designing the concentration camp exhibit around the concept that many prisoners consumed only 300 calories a day. What does 300 calories a day look like? Yet even with great ideas on the table, they seemed reticent to move forward.

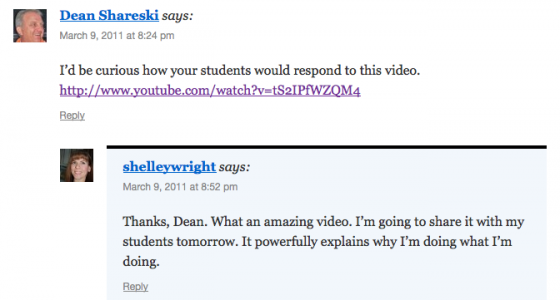

I find that when my students struggle, I struggle as a teacher too, but differently. At times I’m not sure how to facilitate their learning. If I do it for them, they won’t develop the skill. It’s difficult to know how much to let them flail. I find my role, at this point, is to facilitate conversations they don’t know how to have. As I often do in this scenario, I turned to my personal learning network. I blogged about it.

In response to my blog, Dean Shareski left the following comment:

The link Dean suggested is a clip of high school Principal Chris Lehmann speaking about educational change at the Philadelphia TED-x. He begins with a bold statement – “High school stinks” — and goes on to describe what we can do to change that. I was so incredibly moved by his talk that I knew I needed to show my students.

Their response? They burst into applause. They’ve never done that before at the end of a video. Why their response? Because as a class they strongly believe they are not the future. They are right now. And their education is not something they should use in the future, someday. It should matter right now.

I looked at my students and made one simple statement, “This is why we do what we do here. You’ve done your research; now you need to build something that matters.”

We then met in what we’ve come to affectionately call “circle time”. It sounds kindergartenish, but my students love it. Essentially it’s a Socratic circle, where we sit and discuss the matter at hand.

“So,” I asked, “what do you need?”

Silence.

And I remained silent. Finally, one girl spoke up, “I don’t really feel like I know how all these pieces fit together.” Another student: “Yeah, how is it supposed to look like it all is part of the same story?” Me: “So, you feel like you’re lacking an overall theme to direct you?”

A third student spoke up. “Yes, I don’t think I even know what the other groups have done. Maybe we can all share what our groups researched and what we found.” Good idea.

A member of the group that researched the Nazi’s outlined their basic idea. They’d designed their ideas around the three “faces” of the Nazi’s, essentially how the world and Germany viewed the Nazi’s as time progressed. The impetus for their design is creating a photo collage of Hitler made from smaller pictures. (My students have even found a collage maker download, although at this point I’m not sure how well it works.)

All eyes moved to the group who researched the Holocaust victims. I quickly interjected that I thought this group had an amazing idea. In fact, it’s so good, that I said, I would love to see us make this exhibit. One group members head shot up. “Really? Which idea?” You see, many of the members of this group have not been successful in traditional academic classrooms. They seem to lack confidence in their ability to contribute to the project.

I explained that one of the ideas put forth was designing the exhibit around the concept that the average inmate survived, or didn’t survive, on about 300 calories a day. The rest of the students were shocked. They didn’t know that. And a number of students started brainstorming what that could look like. Some of them have since found out that you could eat a small fries from McDonalds, with McNugget sauce. Or ice cream & salad dressing for 300 calories. The discovered this while discussing our exhibit at McDonalds. I’m surprised how much they talk about this class outside of our scheduled class.

Finally, a student commented, “I’m not sure I understand how these will all fit together.”

I grabbed a large roll of newsprint paper, and pulled a long sheet out. While talking about all of this is fine, I know many of my students need to see things. I stated that each group should outline the main points of their research, what they want to include in their exhibit. Then we’ll look to see what commonalities we can find.

Each group gathered around their section of the paper and began outlining and drawing their ideas. It was one of those photo-worthy moments. My students were deeply engaged in their work, debating with their group members about what was important, making connections, drawing the details.

After they were done, they looked for ways to connect the different areas. They wanted it to fit together in a way that made sense to the viewer. Originally, I had figured that each group would design their own exhibit around what they had researched. Finally, an idea popped into my head. I said, “All the ideas fit into the three faces of the Nazis, don’t they? What if we used that as our organizing idea?”

One of the students excitedly stated, “That’s what I said! We could call it Faces of the Holocaust.”

I’m teaching like never before

So that is our exhibit name and our organizing theme. Faces of the Holocaust. It will include three faces the Nazis showed to the world. The first is the propaganda used by the Nazis to deceive the public. The second face is the reality; this is the face the Jewish people, and others persecuted by the Nazis encountered, including the countries that either capitulated to or were overtaken by Hitler’s army. The last face looks at the Nuremberg trials, and the aftermath of the Holocaust

On Monday, we will try to create our mock-up. We’ve decided to create one “face” at a time, starting with the propaganda. Very different than I anticipated. With all students contributing to and creating the same part of the museum, this approach will require a high degree of collaborative effort. My role at this point is to model decision making skills for my students.

My students have commitment issues. And not just small ones, really significant ones. When faced with the open-ended reality that this project can take any form, it’s paralyzing. My role is to help them navigate this and ask questions that clarify.

I plan to teach them the idea of Commander’s Intent, outlined in the book Made to Stick by the Heath brothers. What is the one thing we want our viewer to remember about the “Face One” exhibit? I already know what it is. They’ve said it numerous times. Evil does not always look like evil. Everything added to the exhibit needs to support this one idea. And although there might be other really interesting ideas and artifacts, everything they include must flesh out this one idea. I’m confident now they’ll discover it.

To be honest, this project is so interesting, I want to be part of it. I want to help make and design it, and I’ve never had that impulse while teaching before. I’ve never thought to myself, “wow, I wish I could have been part of the construction of that Hamlet diorama.”

Today was one of those days, when the excitement in my students is so palpable that I can’t believe I get paid to do this. I know for the next two weeks, my room will be a hive of activity. Painting. Creating walls. Replicating important documents. Even in a teacher centred classroom, I was never as engaged or excited as I am now, nor were my students.

There’s a certain shift in role that has to take place. I’m a co-learner with my students. I often ask questions and clarify points my students are confused on. And since I’m side by side with my students, rather than “the sage on the stage,” I find that I’m developing stronger relationships with them, especially those few shy students who say almost nothing in a group. In between coats of paper mache, I have time to have conversations with students that ordinarily I wouldn’t. It doesn’t get much better than this: Collaborating. Communicating. Connecting.

Read all three posts about our Holocaust project:

3. Powerful Project Learning: Outcomes & reflections

2. The Nuts & Bolts of 21st Century Teaching

1. Finding the Courage to Change

Shelley Wright

Latest posts by Shelley Wright (see all)

- Start with Why: The power of student-driven learning - May 8, 2019

- Are You Ready to Join the Slow Education Movement? - August 26, 2014

- Academic Teaching Doesn't Prepare Students for Life - November 7, 2013

Shelly – this is such an instructive piece of writing. I’m sure it will take multiple readings to sort out all the lessons you’ve presented here. One of the first things that strikes me, however, is that this type of student-centered, collaborative, project-based teaching is not instinctive for most teachers. I appreciate how you describe your own unease and how you work through it in order to support your students’ learning. I also appreciate that you recognize that students get overwhelmed or “paralyzed.” To fail at the point you describe could have been devastating, but you taught them to break it into smaller parts, to identify the most significant thing, and to move forward. Finally, I value that you describe your own learning, be it experiential, your PLN, or from a book. Like I said, there are so many valuable lessons for us here. I’m looking forward to sharing and discussing all of them with my colleagues.

Thanks, Renee. There has been a significant learning curve for me, and my students. And my students are well aware that we’re all in this together. I’ve realized my biggest contribution to their education is the skills I possess, that they don’t have, but need.

You’re right that this probably doesn’t come naturally to most of us. I find I have to reflect a lot. I need to know when to step back to problem solve, and then regroup. At times, I’ve felt like this might be a huge mistake. But we learn from mistakes, so that would be okay to.

I’m guessing by the time this whole thing is finished, I will have learned as much as my students. I love my job!

Great article, we just had PD on Echoes and Reflections curriculum from ADL:

http://www.echoesandreflections.org/

Lots of great resources in the curriculum binder, as well as available updates on their website. I’d recommend it as a resource for students working on this project.

Shelley — This is great stuff and really timely for me. I teach MS technology, and the 8th-grade literature teacher and I are about to embark (starting in a couple of weeks) on an ambitious project not unlike yours. The students have read Night by Elie Wiesel and some other Holocaust literature. We just came off a trip to DC where they visited the Holocaust Museum. The lit teacher and I are now going to do a student-centered, collaborative project where each group researches one of five other genocides that have occurred (or are still occuring) in the world. The groups will then create wikis to share their research/ideas, presentations (using their choice of media) that will include first-person interviews (via skype, email, or in person), and some type of physical piece. Our main goal is to get them to form some connections among all these events to look at what they have in common and how they could possibly be predicted or prevented. We are also hoping they make connections between genocide and the bullying/exclusion that is so prevalent in our schools today and how, on a small scale, the way they treat each other DOES matter. Our hope is that they will then be able to share their discoveries and information with other students, parents, and possibly even the larger community. At any rate, we are exactly where you are. We really want the students to be excited about taking ownership but are also very curious (and scared) about how they will accept that reponsibility. I love your comment about there being a lot more silence than you would like. I know we are going to experience that as well. And you’re right. . .they think they will get bailed out, and we will need to resist the impulse to do that. I plan to follow your journey closely and hope to stay in touch with you for suggestions, ideas, and encouragement as we get started in a couple of weeks. Thanks so much for your blog.

Have you read Barbara Colorosa’s The Bully, The Bullied and the Bystander? She does an excellent job talking about these roles in regards to not only genocide, but what happens in our schools.

She also specifically has one on genocide called Extraordinary Evil that deals with how the bullying cycle took place in Rwanda — This is a topic that is very near and dear to my heart. Our next unit after this actually looks at Rwanda & Sudan, and then we’ll be looking at human rights abuses and begin advocating against them.

If you end up creating blogs or wikis, I’d love to see them!

Shelley,

I am the literature teacher working with Gretchen Peterson on the genocide project. I just finished reading Extraordinary Evil by Colorosa, and I was blown away by the connections to be made between bullying and the genocides of the 20th century.

I have been teaching the Holocaust to eighth graders for thirty years. I finally realized I should be broadening my scope to include other genocides, some I actually knew nothing about myself until I started researching. Gretchen is my best friend, team member, and a technology expert! I am totally reliant on her to guide the kids (and teach me!) in the technology portions of this unit.

Like you, I have taught the Holocaust by means of lecture, slide shows, videos, Anne Frank, and Night. The unit we are planning will require a new way of thinking on the part of this sixty-four year old English teacher! We will keep you posted, and thank you for sharing your innovative approach.

Nancy, so glad to hear you’re part of this exciting journey!

I, too, decided to broaden my scope when teaching genocide because my students always said it would never happen again. Wrong. So now I teach Rwanda & Japan.

Last year I had my students create a Pecha Kucha of a genocide, and it was surprising how many genocides occurred in the 20th century alone.

One tool that your students might find really useful, if you haven’t used it before, is dipity. It creates beautiful timelines that you can embed pictures and videos into. That’s what we started our Holocaust unit with.

I can’t wait to see what you come up with!

You might want to check out this link: http://www.youtube.com/user/RootsofOpressiontv. This was a project by high school students who did a similar project (comparing Nazi Germany with current regimes with similar characteristics).

Sounds wonderful… please tell the kids that I said hello.

And take a thousand pictures and post them online… of the process and of the product. We all want to see what you and your students come up with.

Best,

Chris

My kids were thrilled that you said, “hello”. Thanks for the inspiration that you’ve given to me and my students, and many others. One of my colleagues watched your video,was so inspired, and is now thinking of revamping her own classes. Soon there may be two of us at my school!

This just in: Researchers in Texas discover that students learn more when they have more choices and control over the learning experience. Duh!

http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/inside-school-research/2010/12/class_choice_may_spur_student.html

Thanks so much for documenting your own learning so thoughtfully.

What a wonderful piece! You have given me so many ideas. I too have taught a Holocaust Unit and feel that I have always left too much undone. Will reread several times. Looking forward to more observations.

Every year I’ve taught the Holocaust I’ve always felt the same way. Like something was missing. Really, like you’ve said, too much undone. This year, I do not feel that way. My students have learned so much, and have been impacted so deeply. This has been a stunning and rich experience.

Hi Shelley;

I feel so inspired. I agree with what Rene said about it taking multiple readings to take it all in though.

I keep trying little pieces of collaborative, student centred learning in my hs history classes. But often they are small, one class or less, activities. I love how big you’ve made this project; how you were willing to turn over the whole unit. I want to try something like it for an upcoming unit on the cold war in my Canadian history class, but in addition to the paralyzing/fearful moments you talk about with the students, I have my own paralyzing moments a teacher planning this: I hate that my first question (after getting very excited about the possibilities of student engagement and learning) is “how would you/I mark this?” But I am curious, and it will be one of the first questions that gets asked of me after my department PLC reads your post and realizes I want to have us try it.

Please keep us posted on how it goes.

I’m so excited you want to try this. Trust me, it’s worthy. Our project is about a week away from completion. I have students who have not done well in traditional classrooms, scouring books, and internet sources to make their exhibit authentic.

The marking is both qualitative and quantitative. It’s possible to use rubrics for both. Obviously, no exam required. To hear what students have learned they can do blog reflections, or they could create a voice thread. And for the artefacts they create, a rubric can be used as well. If your students are exhibit presenters, again, a presentation rubric would suffice. If you need help with this, contact me at my blog, I have a contact tab,and I’d love to help in any way I can. Good luck!

Shelly, I have been teaching this way at the University level for over a decade and my daughter currently attends a high school that is 100% project based learning. Your project sounds very interesting and I have the same problems you have, even after many years experience teaching this way: 1) students initially are very timid in taking ownership of their work as they have always been directed by the teacher (what if they get it WRONG), and 2) they don’t have the skills needed to analyze, make generalizations based on their analysis, and communicate what they have learned.

With that in mind, I have some suggestions:

1) Make sure you continue to divide up the project into smaller tasks. This helps make the project less intimidating (we’ve never put together a museum before).

2) Develop a different skill for each section of the project (in addition to the content). For example, the first section would be identifying or defining problems, the second section might be online research skills for multi-media, the third section might be organizing information). In addition to the content, you are also providing them with 21st century skills they will need for life long learning (let them know this is the goal).

3) Make sure you have an assessment tool that helps direct your expectations. This might be a rubric, audience feedback (a form they can work from as they are developing their exhibit), peer and teacher review, learning journal entries, group reports/progress reports, or a combination of these more qualitative assessment tools. My daughter’s school also has “content” quizzes, to ensure students are also understanding the content. But these are usually based on more structured readings at the beginning of the project. They also take the form of essays at the end of the project. These all make students more comfortable that they are being graded on established criteria, although try to avoid making that criteria too specific (i.e. the rubric should be assessing skills, not content).

4) Discuss common problems and work out solutions with the class (as you did with developing a vision). Continue to reassure your class that there is no right or wrong answer, multiple solutions, and that the project will be “messy”. You will eventually develop a certain amount of “project efficacy”. But it will take time to develop. Students need a lot of reassurance initially and teacher presence (which is not the same as teacher centered or teacher directed).

What I love about this post is that you can supplant any topic into this structure, and because it is so student-centered, it can be used for any research project. Shakespeare, The Shogun Era, a timeline of inventions…this project-based learning unit with such curtailed use of “sage on the stage” is a powerful and easy to follow guide for many teachers.

When I was teaching 5th grade (I’m a middle school teacher now), we designed our own colonial museum, complete with role-played characters that could be interviewed by those experiencing the museum. The kids researched their created characters, designed their backdrops based on their trades, created an interactive digitized map of their town (courtesy of the kid assigned as the local town cartographer), and rehearsed their scripts which began as journaled quickwrites. It was incredible.

Of course, it couldn’t be the same next year or I would be bored, so this time, the audience was invited to sit in the darkness of a “barn” constructed by the students in the auditorium, surrounded by their created townsfolk as they debated in secret about what to do about housing the British soldiers in their midst. It was scripted this time, based again the student’s writing, edited together by a committee of 5th graders into a cohesive debate. Audience of all ages would come in shifts to see the secret debate and learn about the colonies. After all, those who teach do the learning, and in this case, my students were teaching the whole school and all who dwelled there.

The minute we hand it over to the students is the minute the real educating begins…for us and for them

Thanks so much for this post,

Heather Wolpert-Gawron

What amazing projects you’ve done! I am sold on project-based learning, and now consider myself a PBL advocate. I imagine your students must have learned so much during these projects. I am shocked at how much my students have learned, and the responsibility they’ve taken for their projects.

I will use PBL whenever I can. And you’re right, you can supplant pretty much any topic into this type of learning. Thanks for sharing your experience!

What is most powerful for me about your post and the responses from others is your willingness to share your “unease.” I think this is the biggest hurdle for us as teachers in the 21st century – to put ourselves out there, in a place where we often don’t always know what to do or how to help our kids. I teach in a K- 4 school, yet the angst you expressed so well is what we all feel.

Our staff recently read an article by Rick duFour, “Work Together, But Only if You Want to.” The byline is “We cannot waste another quarter century inviting or encouraging educators to collaborate.” Your blog posting has inspired me. Collaboration was key in moving you along in your practice. Thank you.