Our brains don’t like unresolved issues. We don’t do well with open questions. Hollywood figured out long ago that cliffhangers are sticky — that our brains remember unresolved issues longer than plotlines that just plod along.

Those pioneer producers invented the “cliffhanger” to get you to come back to the cinema, Saturday after Saturday, to see if the cowboy would save the damsel in distress or if the mad scientist would be stopped by the superhero just in the nick of time. The strategy worked, of course, and it became an entertainment staple. No surprise that some of the most memorable episodes in all of television history were season-ending cliffhangers: Who Shot JR or The Simpson’s Mr. Burns? Did Picard really become a Borg? Then there’s the show “24” – pick any episode.

Those pioneer producers invented the “cliffhanger” to get you to come back to the cinema, Saturday after Saturday, to see if the cowboy would save the damsel in distress or if the mad scientist would be stopped by the superhero just in the nick of time. The strategy worked, of course, and it became an entertainment staple. No surprise that some of the most memorable episodes in all of television history were season-ending cliffhangers: Who Shot JR or The Simpson’s Mr. Burns? Did Picard really become a Borg? Then there’s the show “24” – pick any episode.

In fact, cliffhangers in TV series have sort of become the norm to get viewers back after a few months of reruns. And we (that is, our brains) demand that they BE resolved. We get upset when a series we like ends either with an abrupt cancellation or with an ambiguously written finale. The cast of Seinfeld sitting in a jail cell was not nearly as emotionally satisfying as when the helicopter flew off and Hawkeye Pierce saw that BJ Honeycutt had spelled-out “Goodbye” in the rocks on MASH. And The Sopranos… let’s just not go there. Boom? Is that all there is? Boom? Our brains reel.

I suspect that we talk about unresolved endings much more than the ones where everything is nicely wrapped up in the final five minutes. Our brains are trying to end the TV series or movie for us; to do the work that the writers and directors failed to do (at least in our minds).

Our brains want closure

Our cerebral cortex abhors the cliffhanger, be it missing friends or relatives, lost loves, soldiers who remain MIAs, sailors adrift at sea, or TV shows that end without resolution. And one of the interesting things about unresolved issues is that we seem to remember them longer than we do the resolved ones, as we try to fill in the blanks in our brains.

We are hard wired for closure and feel discordant when things don’t end in neat little piles. Perhaps that is why students have such a hard time when we don’t provide them with the answers that they want. “I don’t know, find out on your own” was probably the most hated phrase I used in my classes, but also probably the most useful. After rolling their eyes at me, students would go back and have to resolve the puzzle and find the answers that I wouldn’t just readily give out.

Problem Based Learning (PBL, and if you can’t get past “project” here, see my earlier Voices post) takes full advantage of this neural discordance. When written well, the “Problem” presented through a PBL activity creates a situation where the brain wants to resolve the problem presented. Students create an emotional attachment to the learning because the problem drives the learning, not the other way around. The problem is unresolved, and when there is not an easily solvable solution readily available (no science kit or multiple choice), the brain sets out to resolve the unresolved. And things get delightfully messy.

Several PBL classics

Consider the classic first-grade PBL problem introduced at the beginning of a unit on animal habitats:

Students receive a letter from a student asking them, as animal experts, to help the writer decide if the animal in Grandma’s tree is worth bringing to class as a class pet. A picture is included, but it is so fuzzy that it is unrecognizable at first. Further investigation is required to solve this problem.

Students receive a letter from a student asking them, as animal experts, to help the writer decide if the animal in Grandma’s tree is worth bringing to class as a class pet. A picture is included, but it is so fuzzy that it is unrecognizable at first. Further investigation is required to solve this problem.

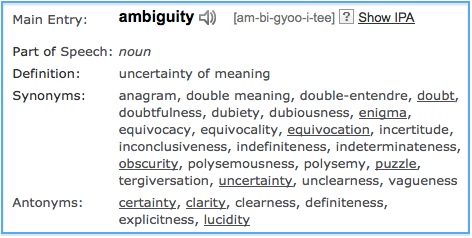

The students are at once presented with a problem where they are treated as “experts” and asked to consider proper animal habitats through the use of an ambiguous, messy problem that presents no single correct answer. Immediately, questions arise:

– What is the animal in grandma’s tree?

– What are the rules for having pets in class?

– What animals are good to keep as pets and which are not?

The questions are not quickly answered resolved in the PBL unit. Indeed, it is up to the students to not only come up with the questions to ask, but also to find the answer.

(Are you curious as to what the animal is in the problem above? Don’t you wish you could see a picture of it so you could decide for yourself if the animal is an appropriate one for a first-grade class to take care of? I’m not telling you. Don’t you hate that? Heading for your search engine?)

Or consider the high school PBL where students are asked to decide if they should allow genetically modified food to continue to be served in the school cafeteria.

This classic PBL is multi-layered because students are placed in differing roles during the activity: farmer, biotech company president, school board member, environmentalist. Again students are not given a specific right or wrong pathway to solve the problem, and since differing people have differing viewpoints, there is no “correct” answer. Questions immediately arise again in the course of simply introducing the unit:

This classic PBL is multi-layered because students are placed in differing roles during the activity: farmer, biotech company president, school board member, environmentalist. Again students are not given a specific right or wrong pathway to solve the problem, and since differing people have differing viewpoints, there is no “correct” answer. Questions immediately arise again in the course of simply introducing the unit:

– What food being served in our cafeteria are we talking about?!

– What does it mean to be genetically modified?

– What is the difference between genetically modified food and food that is selectively bred for specific characteristics?

At the end of the unit, all of the various groups must make a presentation to the “school board.” The way the school board finally will vote is never a given. Indeed, the vote can and does change from class to class, just like in real life. It’s a cliffhanger.

While reading this, were you a bit upset that you weren’t being told why being “genetically modified” might be controversial? Or not being told which foods in the cafeteria were already modified? Your brain started the problem solving process but couldn’t immediately complete it, just like it did with the animal in grandma’s tree. Your were trying to resolve the unresolved. To scratch the cliffhanging itch.

A powerful tool

This type of dissonance is a powerful tool that educators can use. The advantage of PBL (problem based, a.k.a. PrBL) instruction over the “other” PBL (project based) is that dissonance is not an essential characteristic of project based units. Unless it’s a PBL/PrBL hybrid, the neurological conflict simply does not exist in project based learning because the end is already decided.

In problem centered learning, the desired result is not pre-determined and the endpoint is elusive. Carefully constructed problems — sticky and itchy — will cause students to want to pursue the knowledge and skills they require to bring about resolution. As a result, they’ll end up digging more deeply.

Ambiguity, messiness, and lack of resolution are hallmarks of PBL units. And while that may sound like a grading and teaching nightmare (hint: figuring out how to pull it off is your own PBL assignment – there are plenty of ideas out there), PBL creates an environment where students want to solve the problem.

Whether it is a Rubik’s Cube, a video game or a scavenger hunt, unsolved problems can engage students for hours upon hours. The trick is to take the energy that the brain focuses on a particular unresolved situation and move it towards an educational outcome.

If you have colleagues who perhaps think that unresolved problems don’t engage the mind as much as I do, try this very simple trick to show them how the mind wants to have closure:

Start a “Knock Knock” joke, but don’t finish it.

“Knock knock.”

“Whose there?”

When they say “Whose there?” just smile and walk away.

Unresolved wins.

Tim Holt

Latest posts by Tim Holt (see all)

- Problem-Based Learning: Our Brains Abhor Cliffhangers - June 6, 2013

- The Ultimate Education Reform: Messy Learning & Problem Solving - April 19, 2013

- Why Problem-Based Learning Is Better - January 10, 2013

Nice article.

What struck me most was your connecting unresolved events to student learning. I suppose that has a lot to do with their natural curiosity about the world as well Thanks

I am sending this on to a few colleagues.

Tim – fascinating article. I can see how the engagement of students can be enhanced and stimulated “for hours upon hours”.

Great – but what about when the pressures of time just will not allow for this sort of extended exercise? I do a lot of coaching of students for university entrance and other public examinations, where we do not have the luxury of such time to invest.

Having said that, your approach undoubtedly chimes with how we think out brains work – so I shall be giving quite a bit of thought about how I can work your ideas into my teaching. Thanks.

Hi Stephen, Thank you for the comment. I agree that time can be an issue, but I think that PBL does not have to be a long drawn out lesson. (one week tops in manny cases!)

Cliffhangers can engage you for any period of time: a two hour movie or a 30 second commercial.

Sheryl Nussbaum Beach once said to me that “We value the things we make time for.” So, if we are making time for lots of tests, that is what we value. If we make time for curricula that is an inch deep and a mile wide, that is what we value.

I understand the issues of time, but I also know that many things can be wrapped up into PBL units that have the same time requirements of “regular” lessons.

Hello Tim,

I love this post. It is kind of crazy to realize how messy our brain gets anytime we need to figure out a solution. It happens all the time.. I’ve been doing this with my students PBL and it really works. Your post is one of the best I read these days because it is scientifically true that humans we need that adventurous solving issue to put ourselves to work with enthusiasm.

Yeah unresolved wins!!!